Writing Code from Scratch

What to do when you have to come up with your own answers.

Tutorials are great for seeing examples of code and new programming concepts in action. They show you the solution and walk you through the steps to make it work. However, they typically don’t demonstrate the problem solving process that goes into developing the answer in the first place. Writing code “from scratch” requires a set of problem solving skills that tutorials don’t teach. Developers need to see concepts demonstrated, but they also need to learn and practice the process for developing a script on their own. Here is the creative problem solving process I use when programming to come up with solutions when I have to come up with a solution on my own.

1. Write down clearly what the code should do

This step might seem obvious, but clearly stating the goal and being able to reference it as you work makes it easier to focus and makes sure you’re completely clear on what the goal is.

In this example, we’re going to write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one.

2. Sketch it out – on paper and in pseudocode

It’s tempting to jump right into the code and try to start writing. And if you’re an experienced developer, the problem is simple, or you’ve solved a similar problem before, you can probably just go ahead and write out the script. If you don’t have a lot of experience yet or the problem is very complex, it’s helpful to sketch out the logic first before trying to write any code.

Thinking through the logic and trying to translate it into the right syntax at the same time is hard – it requires the brain to do too many things at once so it freezes up. So do one thing at a time. Think through the order and logic of the instructions first, then translate it into code in the next step.

Here’s a couple ways to do sketch a script. One way is to write down the steps logically with pseudocode. Pseudocode is instructions written in plain English (or whatever your primary language is) that roughly resemble the logical order of steps a computer would take.

In our example, it might look like this:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

// Compare the length of the first word and the length of the second word

// If the first word is longer, store it as the longest word, otherwise if the second word is longer, store it as the longest word

// Compare the next word to the longest word

// If the next word is longer, store it as the longest word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

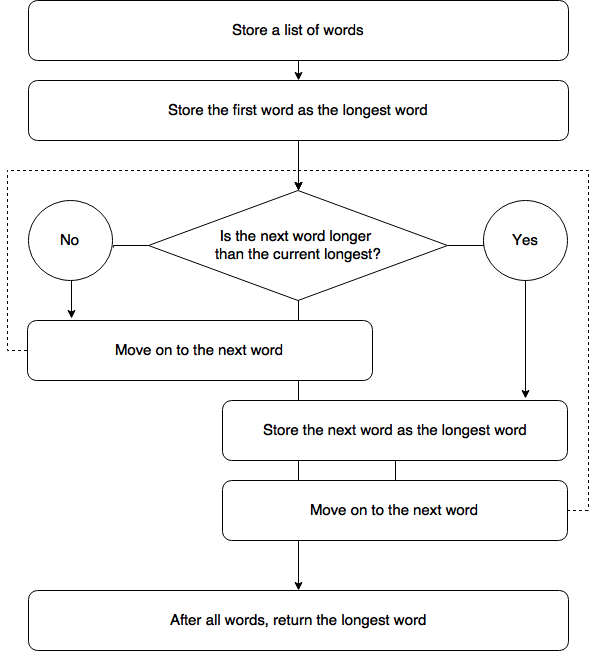

// Return the longest wordThe other option is to sketch out the instructions visually in a flow chart. You can do this in a sketchbook or on the computer. Here’s an example of how that might look:

The logic may not be completely correct after you write it out or sketch it out, and you may not know exactly how to write this in actual code, but that’s okay. You have enough to get started on the next step, and you can come back to this step later if there’s an issue with the logic.

3. Translate each step into code one line at a time

Before beginning this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is that the code you’re writing doesn’t have to be perfect the first time. It’s important to just get one tiny piece of the overall functionality working so you can get some feedback and make some progress. Even if it will have to be adjusted later, each step results in feedback and a few pieces of code you can use moving forward.

Using your pseudocode, break it down into tiny, tiny pieces that you can tackle individually and do them one at a time. If you don’t know how exactly to write something in the correct syntax, this is a good time to do some research and look it up.

In the next example, we’re taking the pseudocode from the previous example and translating one line to store the list of words:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

// Store the current longest word, which is nothing at first

// Loop through the words and compare the length of each to the length of the current longest word

// If the compared word is longer, store it as the current longest word

// Otherwise move on to the next word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

// Return the longest wordAlready at this point you may realize errors in your logic that can be improved, and I made some edits to the pseudocode above to make it more clear.

I’ll translate a few more steps now:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

// Store the current longest word, which is nothing at first

var longestWord;

// Loop through the words and compare the length of each to the length of the current longest word

// If the compared word is longer, store it as the current longest word

// Otherwise move on to the next word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

// Return the longest word

console.log(longestWord);Notice how you don’t need to translate the steps in order. Often it’s helpful to start at the beginning (the input and output) and work toward the middle. Let’s do a few more:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

// Store the current longest word, which is nothing at first

var longestWord;

// Loop through the words

for (var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

console.log(words[i]);

// Compare the length of each to the length of the current longest word

// If the compared word is longer, store it as the current longest word

// Otherwise move on to the next word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

}

// Return the longest word

console.log(longestWord);Notice how I’m using a console.log just to make sure the loop is working before I even try to do the next step of comparing the words. Sometimes lines of pseudocode need to be broken down into even smaller steps.

Testing along the way makes debugging much easier down the road. If you try to write the whole script and then it doesn’t work, you might have no idea where in the script the issue is. If you test along the way, you can move forward with confidence that what you’ve written so far is working. When it comes to debugging, knowledge is power. The more you test, the more you know about how your script is working.

Continuing on:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

// Store the current longest word, which is nothing at first

var longestWord;

// Loop through the words

for (var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

if (words[i].length > longestWord.length) {

longestWord = words[i];

}

// Compare the length of each to the length of the current longest word

// If the compared word is longer, store it as the current longest word

// Otherwise move on to the next word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

}

// Return the longest word

console.log(longestWord);Now we’re comparing the length of each word to the length of longestWord. However, if you run this script, you’ll get an error! We’re trying to compare the length of a word to an undefined variable, longestWord. Since it’s undefined, it doesn’t have a length. Let’s fix that:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

// Store a list of words

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

// Store the current longest word, which is nothing at first

var longestWord;

// Loop through the words

for (var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

// If there is already a word stored as the longest word

if (longestWord) {

console.log("Longest word exists already");

// Compare the length of the current word to the length of the current longest word

// If the current word is longer, store it as the current longest word

if (words[i].length > longestWord.length) {

longestWord = words[i];

}

// Otherwise, store the first word as the longest word

} else {

console.log("No longest word exists, save the first word");

longestWord = words[i];

}

// Otherwise move on to the next word

// Repeat until all words have been compared

}

// Return the longest word

console.log(longestWord);Here we’re checking to see if a word has already been stored as the longest word. If it has, then we compare the current word in the loop to it and determine which is longer. If it hasn’t, we store the first word in the loop as the longest word.

Getting stuck like this happens in the middle of writing almost every script. Expect to go back and revise your pseudocode and do more research to solve problems you get stuck on in the middle. Using console.log to test each step along the way is a great way to see what’s going on with the data as the script runs and solve problems. The best way to solve a problem is to see what the computer is thinking, and the best way to do that is to look at the logs and errors!

That completes the rough draft of our script! It’s looping through the list of words and at the end we see the longest one logged to the console.

4. Iterate

After you have the basic functionality working, you can work on refactoring and improving the code and making it more flexible and reusable. For this example, we’re going to refactor it to be a function that we can reuse with any set of words:

// Goal: Write a script that compares a list of words and determines the longest one

var findLongestWord = function(words) {

var longestWord;

for (var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

if (longestWord) {

if (words[i].length > longestWord.length) {

longestWord = words[i];

}

} else {

longestWord = words[i];

}

}

return longestWord;

};

var words = ["banana", "applesauce", "orange"];

var longestWord = findLongestWord(words);

console.log(longestWord);This process often requires more jumping back and forth between pseudocode and translating into code. It also requires more testing with console.log along the way, making sure that each step works.

Rough drafts are specific, final drafts are modular

When you go through this process, usually the code moves from specific, inflexible versions to more flexible and abstract code. Specific means that it can only be used to do one thing or in one situation, and abstract means it’s reusable and able to be used in multiple situations. In this example, we made the code work for one specific set of data, then made it an abstract reusable function.

This is part of the sketching process when writing code—don’t expect it to be perfectly modular right away. Get it working in any way you can even if it’s imperfect, then go back and improve it once you’ve made some progress. The thing to avoid is making no progress for a long time because being stuck will eventually completely erode your motivation. It’s a lot more fun to solve problems one step at a time than be overwhelmed by the whole mountain.

This process doesn’t have to be followed every time–as you gain experience you become more fluent in writing code so you don’t need as many steps and you can skip ahead. However, even experienced developers run into complex problems and need to step back and go through a process similar to this one to find a solution.

Questions, comment, ideas? Let’s talk on Twitter!